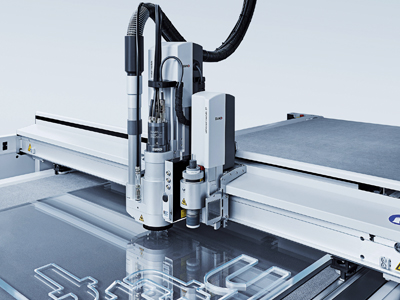

Zünd’s routing module handles rigid substrates such as acrylic, MDF and aluminium

There’s an argument that printing may be important but it’s finishing that turns it into the goods that the customer actually pays for. Simon Eccles looks at where finishing is for digital print.

Next year it will be a quarter century since the Ipex of 1993 that’s generally regarded as the launchpad for the digital printing revolution, marked by the launch of the Indigo and Xeikon full colour production presses. Finishing manufacturers were a little slow off the mark in developing systems to meet the common characteristics of digital print: short runs; quick turnarounds; variable data that may need to be kept in order; oily toners that complicate feeding and laminating but may crack on folding; and little or no waste to use on downstream make-ready.

However by the turn of the century and certainly by Ipex 2002, they were building machines tailored to the smaller SRA3 formats of most digital printers of the time. More importantly, they were gaining servo motors for fast computer-controlled set-up, often with little or no make-ready – especially important for short print runs with no overs to play with – and memories to store common jobs for repeats.

B2 digital presses remain comparatively rare – only HP Indigos and Xeikons have sold in significant numbers so far. However, a key market for sheet-fed Indigos at least is B2 litho printers who can use their current finishing equipment, so there’s less need to reinvest in digital-specific machines. Shorter runs and demand for fast low-waste finishing make-readies is just as relevant to litho as digital in B2 though, so the latest machines have similar automation to the smaller format models.

Here we’re looking across a broad range of finishing systems for general commercial needs. We’ve taken booklet makers and wire binders as the top end of the binding requirements, as we’ve considered more dedicated book equipment such as saddle stitchers and perfect binders in other issues lately.

Coaters and laminators

Coaters and laminators started out with the simple purpose of putting a protective layer over (usually) print. Coaters apply a clear liquid varnish, while laminators apply a plastic film, using either pressure alone for cold lamination, or heat and pressure for thermal lamination. If you wanted high gloss as well you would use a UV liquid varnish. UV varnishing and laminating was often done by outside specialists.

Digital print, coupled with web-to-print ordering, often needs fast turnaround, which led to a demand for systems that were affordable enough to bring in-house. This has been a major trend of the last decade. Thermal laminators and film adhesives needed to be redesigned for digital toner print, where fuser oil prevented adhesion with older systems; new adhesives and higher pressures were needed.

There’s now a useful choice of smallish digital-friendly laminators at attractive prices, typified by Vivid’s Matrix sheetfed 46 and 65 cm width models, Foliant’s extensive range of Czech-built B3 and B2 models ranging from manual to fully automatic; and the Bagel Systems range sold by Terry Cooper services, with SRA3, B3 and B2 digital-friendly models. Intec’s ColorFlare is a compact dual laminator and foiler that retails for under £10,000, can handle paper up to 1219mm at up to 400gsm and works with most digital and litho sheets. If you want heavy duty continuous production, the smaller UK-made Autobond models fit the bill.

Vivid’s Matrix laminator allows variable foiling and holographic effects

Tarrant Machinery imports the Italian Synergy Laminating range, with a choice of thermal or water-based wet laminating or hybrids with both. These start with the relatively small Digit models in 56 and 76 cm widths, for up to 40 cycles per minute, with the fastest thermal model being the Fast HS112 for up to 100 metres per minute.

The past few years have seen laminators being adapted to apply digital embellishment effects, such as metallic or diffraction foils and spot gloss, using additional feeders for hot foils, where the adhesive adheres to digitally printed toner. We’ve covered those in recent editions of Digital Printer, most recently in October – including the cover.

Vivid reckons it was the first to develop that for its Matrix series, but others have followed, including Korean maker GMP with a system called Sleeking; and Intec with its own take on GMP machines. At the high end Autobond offers either cold foiling using its inline SUV inkjets, or hot foiling using toner print. Leonhard Kurz also offers SRA3 and B2 toner-based hot foiling machines called DM-Liner and has also introduced a dedicated UV inkjet based cold foiler.

Dedicated digital spot UV gloss printers started appearing at drupa 2008, with MGI’s first JetVarnish, which is now available as a range of machines from label size up to B1. Scodix upped the game in 2010 with its raised and texturing super-clear gloss UV varnish system (now called Sense) that simulates embossing heights up to 250 microns, and again has a range of B1 and B2 machines. MGI followed with its JetVarnish 3D and upped the stakes with a metallic foiling option, followed a year or so later by Scodix. Czech maker Komfi introduced its B3 and B2 Spotmatic digital spot UV glossers (sold via Friedheim), though they are not especially intended for raised effects. At drupa 2016 Duplo entered the market with its DuSense DDC-810 system, able to produce raised clear gloss effects up to 80 microns on long-B3 format sheets.

Morgana’s Laminator Pro 450

Booklet makers and multifinishers

This is a broad area of useful multifunction devices that range from simple staplers and folders that may run inline with even light production digital presses and copiers, through to complex modular finishing units that can be configured for all sorts of finished items, some of which integrate into factory networks via JDF or similar.

Examples are the KASfold range with three models offering different numbers of stitches and the option of a jogger and collator. Morgana has an extensive range of booklet makers, starting with the BM 50 Bookletmaker to take up to 22 sheets of 80gsm paper, at up to 1800 per hour, ranging up to machines for thicker booklets with options such as collators. Duplo offers three main models of booklet maker (the 150 and higher-speed 300 for SRA3 and the 600i for larger sheets that allow landscape A4 booklets). The 600i can be fitted inline with Ricoh digital presses.

Watkiss Automation is notable for its SquareBack series of nearline and inline document makers that use wire stitches but form a square spine that stacks flat, look good on a bookshelf and can take a spine title.

Multifinishers are the next step up from booklet makers, being advanced multipurpose machines that can usually take drop-in modules to handle several types of finishing in one pass. Duplo largely pioneered the idea with its DC-645 in the mid-2000s, which has now been expanded to three main models all on their second generation, the top ones with optional JDF cross-connectivity to HP Smartstream Designer front ends.

For example the mid-range DC-646i includes a marginal slitter module, a rotary tool module, two centre slitter modules, a creaser tool and a cross knife tool. Optional modules will perforate, slit-score, micro-perf/score in both directions. It can create up to eight lengthways slits, 25 crosscuts and 20 creases in one pass.

Horizon’s SmartSlitter (distributed by IFS) is the main rival to Duplo’s high end DC 745i model, able to slit, gutter cut, edge trim, cross-cut, perforate, and crease in one pass. It integrates with Horizon’s pXnet production network.

Uchida also offers the Aerocut One and more versatile Aerocut Prime multifinishers, sold though Morgana in the UK. These offer creasing, slitting and cutting in one pass. The One’s options include a cross-perfing unit and a bar code reader for quick job setup; these are standard on the Prime.

Wire binders

Wire binding (often generically called Wire-O though that’s actually a trade name) is a popular alternative to simple stitching for documents that need to be opened flat or folded back on themselves, and also very commonly used for calendars. There’s a choice of looped ring wire or true spiral binding, while plastic combs and coils are closely related and can usually use the same punching machines.

James Burns International (JBI) and Renz are two of the biggest players in this market, both with products for punching and binding at all levels from desktop up to large-scale production.

Creasers and folders

Creasers can be the simplest of finishing equipment, starting with little manual knife or platen machines costing from £150 or so, or motorised machines such as the Creasematic 150 sold through Encore Machinery.

If you don’t mind hand folding, creasers are a very economical way to get a quality fold on paper and card, but are also particularly useful with dry toner print on papers, that may otherwise crack on folding.

Morgana’s AutoCreaser range for example runs from the entry level 33 (33cm width) and 50 (50cm), which include a memory for standard fold positions, through the Pro 385 with deep pile feeder, and then to the DigiFold series of combined creaser-folders for up to 385 x 900mm sheets with parallel folds.

Folders of course automate the process to produce stacks of folded items, with provision to put several folds in the same sheet, and some with cross-folds to create 8+ page sections for binding. However, the needs of digital and conventional print are almost identical by the folding stage, unless you opt for an inline or nearline collator for non-digital sheets.

One of the main functions of larger format folders is to create book and booklet sections from large multipage sheets, but these are less necessary for most digital work due to the predominance of relatively small format presses.

If you only need small formats, MBO for instance offers the compact T 460 for 46 x 66cm sheets. Typically it can produce four or six page sections, gatefolds or folding end sheets. There’s also the even smaller T 535 for 35 x 50cm sheets.

Folder-gluers extend the range of products that can be made, creating finished items such as folders with and without capacity pockets, greeting cards, cross-folders and CD pockets, as well as cartons.

Kama’s ProFold 74 for instance, can handle all these applications, including cartons with crash-lock bases, starting with sheets up to 74cm wide.

Collators

On the whole you don’t need these for a digital press, where the ability for every sheet to be different means you can print ready-collated sets. However, many digital press users also have offset presses and some jobs demand a mix of digital and non-digital sheets to be combined. For those cases you’ll need a hybrid system that combines a sheet feeder with a counter and possible bar code verification (for the digital sets) with a normal multi-station collator for the non-digital sheets.

For example Duplo can put a conventional collator inline with its compact SRA3+ 150 booklet maker as well as the faster modular 300 and the somewhat larger 600i (which can create landscape A4 booklets). Morgana’s BM60/61 and System 2000 Bookletmakers also have a collator option.

Cutters

For long runs guillotines have always been the machine of choice. Programmable guillotines were the first finishing machines to adopt computer memories, as long ago as the 1970s. There’s no difference in the requirements of guillotines for the shorter runs needed by a lot of digital print, except perhaps that if you only print smaller formats then you can save space by installing a narrower throat machine.

A good example is the Grafcut 52H guillotine sold via Terry Cooper Services, which has a 52cm cutting width and 52cm depth, suited to most SRA3 presses though not the long sheet types. There’s a 73 x 73cm version too, but if you need larger then TCS sells its own-brand CCS Premier models for heavy duty work in widths from 78 to 168cm.

German manufacturer Polar sells an entry level small 6cm width guillotine in recent years under the brand name Mohr, distributed in the UK by Watkiss. Likewise Bauman-Wohlenberg’s guillotine range (distributed by Friedheim) starts at 76cm wide, but even the entry level models have touch screen controls and refinements such as an “electronic handwheel” for fine control of the backgauge, which is actually driven by a servo motor. Schneider Senator, another Friedheim distributorship offers 78 and 92cm models as its entry level, with all versions now having 15-inch touch screens with an icon based user interface.

The Baumann-Wohlenberg 115 guillotine features fully automatic touch screen control

The question is more whether the work you do justifies a guillotine, or whether another form of cutter will do the job. The multi-function modular systems we look at elsewhere often include cutting and scoring wheels for one direction, with knife cutters or creasers in the other. Alternatively, cutting and scoring wheels from the likes of Tech-ni-Fold can be fitted to virtually any folder or other machine delivery. The company also sells standalone crease/cut/perf wheel machines with manual or auto feeders under the CreaseStream brand. A recent development by Tech-ni-Fold is a wheel set to put double scores on fold lines, preventing cracking the inside as well as outside of double-sided toner print.

For die cutting work in packaging the trusty converted platen or letterpress cylinder press soldiers on in many print works even when all around is digital. For higher volumes some sort of frame-type autoplaten with built-in waste stripping can be handy. Germany’s Kama has offered compact ProCut 76 B2 machines and the very small ProCut 58 B3 machine for the past decade. In addition to the small formats, which suits digital presses, the make-readies are also fast. They can also be used for hot foiling and embossing.

Bobst, best known for full-sized high throughput autoplatens, has also put a lot of work into fast make-ready too. Its Visioncut 106 models are versatile all-rounders intended for applications such as greetings cards and labels as well as folding cartons. While the 76 x 106cm format is wider than you’d need for most digital presses today, it would suit very long-sheet, nominally SRA3+ models.

Rotary die-cutters used to be big expensive machines that were mainly used for very long runs or frequently repeated intricate work. The past few years has seen a trend for prices to come down and for them to be offered for shorter runs, including narrow width digital print work.

The dies are etched into thin and relatively flexible metal plates that attach to magnetic steel impression cylinders. Changeovers are quick and easy and so is setting up. The dies are fairly expensive initially, but they can be reused many times, so they work best with standard shapes that are repeated often enough to amortise the costs over a reasonable period.

Switzerland-based Bograma was one of the first into this new sector. Its BSR Servo machines can be run inline with folders, mailers or other finishers. The lower cost BSR 550 Basic machine was introduced at drupa as a standalone system intended for short to medium runs of small packaging items or labels. These machines take sheets up to 550mm wide and can handle sheets from A4 up to B2 size at up to 12,000 cycles per hour.

Duplo introduced a rotary die-cutter, the PFi-300 Di-Cut, at drupa 2016 and is now delivering it. This handles sheets from A4 to 364 x 515mm at up to 50 sheets per minute with automatic position correction. Horizon introduced its RD-4055 die-cutter a couple of years ago. This takes sheets up to 400 x 550mm and runs at up to 6000 cycles per hour.

The ColorCut FB520, FB600 and FB900 are digital die-cutters from Intec that the company says can cut – to a depth of 0.6mm – and crease card (up to 450gsm) or kiss-cut labels; an Adobe Illustrator plug-in allows for any shape of cut or crease and the flatbed units start from just under £5000.

Lasers

We’ve covered the development of laser cutters over the years. On the face of it they’re a good option for digital print, as they fit in with the needs for on-demand, short runs and even variable data, with no dies, make-ready or setup. Having no dies cuts costs and speeds make-ready, while the ability to vapourise waste in tight spaces means that very delicate filigree work is easy to achieve.

There’s an extensive choice on the market, from small format hand-fed cabinet types costing a few thousand pounds, through larger hand-fed and hand-positioned flatbed table types costing tens of thousands, up to automatically loaded and unloaded belt-driven mechanised lasers that tend to cost £150,000 and above.

The LaserSharp STP from LasX is barcode driven to personalise with variable data cutting, engraving, and perforating of patterns

Belt-fed continuous motion machines tend to get the most press attention – prominent examples are the LasX Lasersharp range, themediahouse’s B2 motioncutter, both with pile or continuous feeders and robotic unloader options; and Trotec Laser whose GS1200 includes a flat pile feeder and a sheet stacker. Chinese Hans Gronhi (sold via Printers Superstore) has a range of four laser cutters in a choice of sizes with manual or autoloading.

Hand-feeding is often quick enough for short runs, so manufacturers such as HPC Laser are certainly worth considering. Trotec makes manual feed tables from 1245 x 710mm up to 2210 x 3210mm that can take multiple items at once. Polar, best known for guillotines, dipped a toe in the water with its own handfed B2 DigiCut cabinet laser, introduced a couple of years ago.

At the top end is Highcon, with the growing Euclid range of digital cutting and creasing systems in B2 and B1 format. These use multiple lasers for fast cutting but the really clever bit is the DART system that creates creasing rules from extruded and UV-hardened photopolymer. There are only two installations in the UK (out of more than 50 world-wide) but a recent deal between Highcon and press maker Komori Europe may increase the profile.

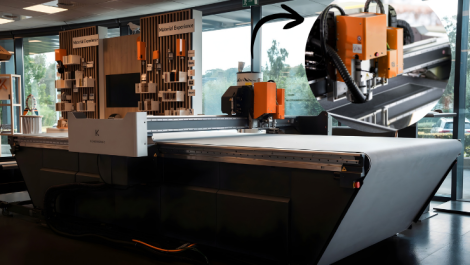

Tables

Digitally controlled cutting tables, also called finishing or plotting tables, are usually associated with large format printing rather than commercial work. However there are some small models of about B2 size, notably from Mimaki, while larger models with automatic registration (as supplied by AXYZ, DYSS, Esko Kongsberg, Valiani, Zünd and others) can handle several sheets at once with no need for precise positioning on the bed. They are slower than physical die-cutters, but have the advantage that they don’t need dies. They’re also usually slower than lasers, but have the advantage of greater versatility – in particular they can form proper creases and can often do shaped routing and v-cuts of thicker materials.

Mimaki’s compact hand fed cutting table, CFL-605RT, has a bed size of 610 x 510mm and a footprint of just 1320 x 1045 mm. It’s mainly intended to complement the company’s UJF family of ‘baby’ UV-cured flatbed inkjets, but work just the same with sheets from any other process.

Read the full November issue of Digital Printer here. Subscribe to the magazine for free – register your details here.