Taking the mono load – Ashford Colour Press’s Domino K630i

Book production is seeing inkjet presses continue their apparently irresistible march, with increasing quality, productivity and substrate flexibility, finds Simon Eccles.

Book printing was one of the first applications for high speed digital presses, dating back almost a quarter of a century now. Back then they were all continuous-feed toner-based presses and all but the Xeikon models were strictly monochrome. The introduction of fast continuous-feed inkjet presses in the late 2000s took speeds up (the fastest then hit 300m/min), but the water-based inks introduced complications with drying and absorption into the substrate.

Despite this, and the fact that inkjets have higher capital costs than toner presses, the cost per copy is a lot less. ‘It depends on the customer, but you can get a third to 50 percent reduction in cost if you do it correctly with inkjet compared to toner,’ says Bryan Palphreyman, product manager for digital printing solutions at Domino Printing Sciences.

Monochrome configurations of inkjet web presses have long been offered by Canon/Océ, HP and Kodak in particular, joined relatively recently by Domino. Océ (now owned by Canon) was a pioneer in fast black and white continuous toner presses for books in the 1990s. It introduced JetStream continuous inkjets in 2008, followed by the ColorStream presses, which essentially put JetStream print engines onto the chassis of the toner-based VarioStreams. Thus a ColorStream unit can replace a VarioStream one and can use the same inline and near-line finishing equipment.

In 2014 the company announced ImageStream, a 760mm width web inkjet with new inks that can print on uncoated offset papers. In February this year came the announcement of ProStream, a quality-oriented 565mm width continuous inkjet. This uses a new resin ink plus Canon’s ColorGrip on-press primer, for quality claimed to “exceed offset colour gamut”, though its maximum speed is a relatively modest 80m/minute.

The long read – Canon/Océ ProStream, introduced earlier this year, is claimed to beat offset colour gamut

Canon says it is also seeing interest in the book format for its B3 sheet-fed inkjet i300, introduced in 2015 with quality enhancements announced at drupa 2016. This can print up to 300 A4 pages/min. It also uses ColorGrip primer printing for uncoated stocks. A detuned entry level 200 ppm i200 was announced in April – this can be field upgraded to an i300 later if needed.

Kodak’s 2010 Prosper 5000XL colour inkjet was a slow starter, until replaced by the much improved 6000. However its accompanying 1000 mono press sold well into the books market, then got a major boost with the second-generation 1000 Plus in 2015, with a speed boost from 200 to 300m/min.

Inkjet ubiquity

Will Mansfield, Kodak’s worldwide director of marketing and sales for enterprise inkjet systems, says: ‘Every publisher in the world now is using inkjets for short-run books. Some 90% of our black and white inkjets are printing books. More and more books now are only ever printed inkjet and only the really big sellers need litho.

‘The colour book market is growing horizontally, and also deeper, on more challenging paper types,’ he adds. ‘The market is now asking to go beyond “pleasing colour” for subjects such as scientific, travel, cookbooks and speciality publications. Our unique ability with the Prosper 6000 is to print on gloss paper at a speed and quality that nobody else has. Part of this is due to our ink and our intra-station drying.

‘Our Stream printheads are continuous flow, which don’t have the blocking problems of drop-on-demand and we can formulate our inks for more effective drying on gloss paper. In the black and white market, most Prosper users do not need pre-treatment at all.’

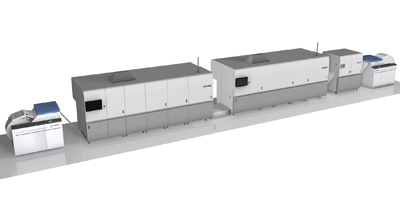

Domino’s K630i monochrome inkjet press runs at 150m/min and has a choice of three print widths up to 540mm. It’s very much aimed at the books market, says Mr Palphreyman, and Domino has put a lot of effort into integration with finishing lines. One has gone to Ashford Colour Press in Gosport to print books (see p36 for more), and a second UK installation is about to be announced. Mr Palphreyman says: ‘At Ashford Press we effectively gave them 30% colour capability back on their HPs, because we took all the mono work off the colour presses.’

FujiFilm’s Jet Press 720S, a sheet-fed B2 model originally aimed at high quality photobook work is also now being promoted for mid-quality books on standard offset stocks. ‘Most of our commercial customers will also print books-on-demand,’ says Mark Stephenson, product manager for digital printing and press systems at Fujifilm Europe.

The stock flexibility comes about because the Fuji ink contains coagulating agents that reduce absorption into the papers. ‘The wide colour gamut of the 720S looks similar to UV offset, but it’s digital,’ says Mr Stephenson. Although the B2 format works for perfect binding, one limitation is that saddle stitchers designed for pre-collated digital print so far only support SRA3 sheets.

Is UV the answer?

Konica Minolta reckons it has another answer to the paper issue, with its sheet-fed B2 format AccurioJet KM-1 inkjet press. Mark Hinder, head of market development in Europe, explains: ‘A major advantage of this press is that it uses UV-cured ink that can be printed directly onto standard offset substrates without any pre-treatment or damaging effects caused by excessive heat drying. This provides real cost efficiencies for printers, especially if they standardise their stocks to maximise their purchasing power.’

Although the company hasn’t named any users “due to confidentiality clauses”, it reckons that most of the KM-1 deliveries so far are being used at least in part for book printing. Mr Hinder says this is thanks to the quality of print on normal paper stocks, plus the ability to print high gloss colour covers.

‘The AccurioJet KM-1 is allowing book printers to experiment with the launch of medium-to-large work not previously available, such as heavily textured materials and plastics,’ he adds. ‘This gives creative options for publishers in an extremely competitive market.’

Screen was shipping inkjet web presses some years before HP and Kodak, showing its first TruePress Jet520 at Ipex 2006. The TPJ 520 HD offers a combination of 150m/min speed with decent resolution, but the most interesting aspect is its new SC inks. These have a relatively high polymer content, so no pre-treatment is needed to print on offset stocks.

‘Print quality matches and in some cases even surpasses offset quality,’ claims Screen’s sales manager Patrick Jud. ‘Hubert & Co recently invested in Germany’s first Truepress Jet520 HD with SC inks. At a technology demonstration for its publishing customers, feedback received was that customers didn’t want to change substrates just because of a change of technology at the printers. SC inks made it possible.’

Ricoh sells lightly modified versions of the Screen inkjets in its InfoPrint range, and over the years has often shipped more of these in Europe than Screen. Ricoh’s version of the screen TPJ 520 HD is called InfoPrint VC60000. The hardware is the same, but Ricoh has not adopted the SC inks, says Tim Taylor, head of continuous feed market for Ricoh Europe. ‘At the moment we use the undercoater with standard inks, as we think this has a greater flexibility of substrates and brightness in printing.’

Paper feed – Ricoh’s VC60000 prints “fast” in mono on uncoated offset stock and at full speed on gloss inkjet papers

He also says that the offset papers argument has less weight that it once did. The press can print on gloss inkjet paper at full speed, or rather slower on a gloss offset paper. There’s no issue in printing fast black and white on standard uncoated offset papers, he says. ‘That’s why we have kept to the standard ink. You don’t need to undercoat and you benefit from a much cheaper ink.’

So far Ricoh has not followed the herd by producing a cut sheet inkjet press. Instead it stresses the continuous-feed VC60000’s ability in a mixed commercial and book environment. ‘Where we see the VC6000 fitting is that it creates the opportunity for trade publishers to adopt lower inventory and stock-replacement colour books,’ says Mr Taylor. ‘You can genuinely print a cookery book or a gardening book or another “nice to own” book. The quality on coated paper is absolutely good enough.’

Xerox essentially invented toner technology, but has accelerated its move into continuous feed inkjet since it bought French company Impika in 2013. It has dropped its continuous-feed toner presses but continues to sell colour sheet-fed presses for book work as well as all sorts of other commercial work. It has kept the Impika name on inkjets introduced before the takeover, but subsequent presses have Xerox names: Trivor 2400 (a mid-range continuous inkjet) and Rialto 900 (a very compact roll-to-sheet inkjet press, taking 250mm width rolls and producing cut A4 documents on plain paper). There is also the US-developed Brenva, a sheet-fed B3 inkjet press costing under £500,000.

Kevin O’Donnell, head of marketing for graphic communications and production systems at Xerox UK, says ‘What we’re seeing is the higher and mid-volume digital book printers all having inkjet capability. One of the things we were discussing at the Book Forum recently (see p10) was a different approach to the papers that are being run. Instead of pre-coating we use high fusion inks with the Trivor, which allow you to print on untreated offset stock. This gives a different economic equation to books without losing the productivity and automation and all the things you’d expect from inkjet. We put the intelligence in the ink so we don’t need pre-treatment.’

Speed and substrate choice have been seen as limiting factors in book production but the variety of approaches taken by manufacturers seems to be knocking down those objections one by one.

Read the full August issue of Digital Printer magazine here. Subscribe to the magazine for free – register your details here.