Barbieri’s latest SpectroPad spectrophotometer was launched at drupa 2016 and can be used with digital print

Colour management for litho is pretty well sorted, but the same isn’t true for digital print, says Simon Eccles.

Consistency and predictability are the main goals of most printing processes, digital included. You want to be able to reproduce a print job in a way the client expects, and all the copies of the job should be pretty well the same during the print run and also if the job is repeated next month.

Calibration and colour profiling is the usual way to get digital (or analogue) presses to reproduce colours accurately despite variables between devices, papers and environments. ICC profiles are the most commonly used and these work especially well for RGB workflows with in-RIP separations, which are common with wide-gamut digital print processes.

If you are receiving CMYK separated files, and especially if you want your press’s results to match another press or process, then device link profiles may work better. These convert directly from one device’s CMYK to another without losing the black separations along the way.

For instance, GMG’s ColorServer 5.0 will run non-ICC based colour conversions to the desired CMYK colours from incoming CMYK components in PDF job files, while also automatically converting any RGB or spot colours to process.

CGS’ Oris Press Matcher Web has similar aims, controlling the grey balance while supporting spot colours and inks additional to the process set where needed. Bodoni supplies the German Color Logic’s ZePrA, a lower-cost solution that automatically handles colour conversion of PDF and bitmap files with ICC or device link profiles.

Working to standards

Consistency within your own print works is one thing, but it’s useful to be able to have something to show to clients. This is where working to standards comes in. These are mainly about methods of working to achieve and then maintain colour accuracy and consistency, with measurements and monitoring that report back to press operators, factory managers and customers.

Some companies set their own standards, but others prefer to work with externally set – and recognised – ones. ISO 12647 is the best known family of these. Over the past decade this has been widely adopted as a system of working with colour management that’s accepted by large clients. There are process-specific subsets, of which 12647-2 for CMYK offset lithography is the most widely used.

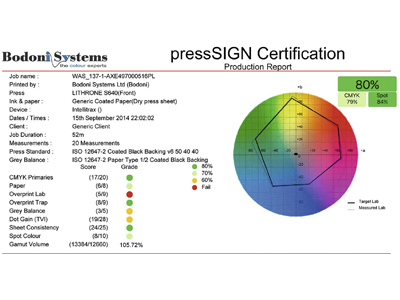

Bodoni’s PressSign displays a printable certification showing compliance with the target standard – ISO 12647-2 in this case

Analysis tools such as Alwan Color Expertise’s PrintStandardizer, Bodoni’s PressSign 8, CGS’ Oris Certified Web, Mellow Colour’s PrintSpec and X-Rite’s packaging-centric ColorCert allow you to print to ISO 12647 or other international or in-house standards, using colour strips printed within the job. The software shows quick pass/fail indicators for operators, usually with job-specific or longer-term detailed reports that can be shown to customers to prove compliance with the standard.

The problem lies with fitting digital processes into that sort of standard. There is still no real implementation of ISO 12647 for digital print, mainly because there are so many different print engine technologies, with no standards for the gamuts of inks and toners – most are wider gamut than offset (so able to reproduce more spot colours and also potentially allowing better photographic reproduction), but each has its own characteristics. There is the 12647-7 standard for hard-copy proofing on digital printers, but the ISO specifically excludes it for production printing.

An inherent weakness of ISO 12647 is that it describes process tolerances, not final results. A job might be printed perfectly with 12647-2 for CMYK offset, but it may not look the same as the same job printed flexo to 12647-6.

Another weakness is that 12647 assumes the use of “reference substrates”, that is standardised papers. As Elie Khoury, managing director of colour management developer Alwan Color Expertise, explains, ‘In real life printers don’t print on ISO-defined papers. If I have a yellowish paper then a blue ink will print greener, but the standard is silent on this.’

Stalled alternative is PASsable

ISO 21647-2/2013 did introduce some extra reference papers, but the real answer for digital was supposed to be another standard, ISO 15339. However it fell at the final hurdle in 2014 and was not ratified as an international standard, because the European and Japanese ISO committee members felt that because it was in essence the US Gracol G7 standard and didn’t address global requirements enough. 15339 is now a “PAS” (publicly available specification), which means that anyone can work within its specifications, but they are not an official ISO standard.

Ian Reid, managing director of Bodoni, explains, ‘15339 uses a grey component as standard. As the gamut of the colour that you can print varies depending on the process, the grey stays the same and therefore there is a better correspondence in the appearance.’ Seven data sets cover colour gamuts from CMYK newsprint up to wide-gamut digital inkjets.

Mr Khoury say that 12647 and 15339 don’t contradict each other, but that ‘12647 guarantees that your press is running to standard, while 15339 guarantees that you’re printing the right colours.’

Mr Khoury says that the US market still tends to use G7, adding that ‘in Europe, offset printers have adopted ISO 12647-2 and have no reason to change; however, for other printing processes such as digital and flexo, we often use G7 calibration in order to get more neutral gray balance.’

Quite a lot of people just take the 12647-2 litho standard and work to that for digital print. It helps when working with mixed process campaigns. However, this limits you to the abilities of CMYK offset. Some printers get around this by using 12647-2 for colours that can be achieved by CMYK litho, then using the wider digital gamut for colours that would need additional spot colours in litho. This isn’t “true” 12647-2, which doesn’t allow for additional colours, but it can still be demonstrated to be consistent using the various measuring tools.

Measurement systems

X-Rite is the major supplier of measurement instruments for both profiling and colour-bar monitoring. Its systems start with the i1 family, based around the versatile i1Pro 2 spectrophotometer, profiling software and various attachments. X-Rite also supplies IntelliTrax2, a motorised scanner for reading colour bars on press pulls.

Barbieri targeted large format inkjet profiling with its earlier devices. However at Drupa last year it introduced SpectroPad, a modern battery-operated patch reader that’s specifically intended for digital presses, as well as proofing to ISO 12647-7.

Techkon is another significant supplier of measuring instruments, including a modern range for pressrooms. Its latest SpectroDrive is a versatile motorised strip spectrophotometer for quickly reading colour bars, with a removable head that allows hand-held readings of other coloured items.

Colour standardisation for digital print remains more of a black art than you’d expect. This is good news for expert colour consultants, but it would be nice if the push-button simplicity of measuring and profiling systems could one day apply to the whole digital colour workflow.

Read the full June/July issue here