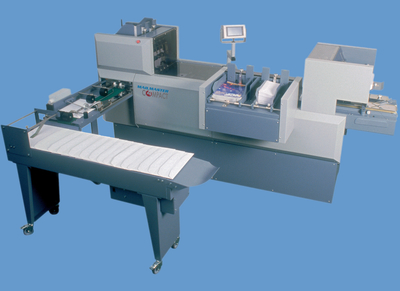

The KAS Mailmaster Compact has a small footprint for limited space installations, but can handle 5,000 envelopes per hour

At what point should a printer consider bringing mailing systems inhouse rather than using an outside specialist? Simon Eccles talks to KAS Paper Systems’ Stephen Hampstead about decision factors.

One of the big benefits of running a digital press is that variable data comes as part of the deal. Small printers do not always need an exotic content management system to take advantage of this, as standard Adobe InDesign and QuarkXPress come with basic mail merging out of the box. In many cases it is common for more elaborate VDP software to be included with a workflow system to sweeten the deal.

But having a mail merging ability, or more, rather leads to the next question: how to do the mailing, and who should do the mailing? According to Addressing & Mailing Systems (AMS) the average person ‘can fill 100 envelopes per hour by hand; this is a costly process if you send out thousands of letters and invoices per month’. So automation soon becomes a necessity. The easiest solution is to ship off larger quantities to a dedicated mailing house and let them worry about investment and accuracy.

However at some point it will start to look beneficial to bring some or all of your mailing inhouse. What that point may be is explored later down this page.

The core system for mailing is an insertion system. Generally this will collate, fold, insert and seal your postal mail in a single process. Some will print the envelope on the fly, others use pre-printed envelopes. If you have personalised contents (ie other than ‘Dear Sir or Madam,’ then you will either have to use window envelopes or go to the next stage of matching inner contents to the outer addresses.

There is a huge range of mailing systems available, ranging from basic £6,000 desktop envelope-stuffers through to super-fast £100,000 to £200,000 lines from Boewe, CMC Machinery, Muller Martini, Pitney Bowes or W&D, jumping up to a couple of million for a ‘white paper’ integrated HP digital web press and envelope-forming line from Pitney Bowes. Or you can just ship the jobs off to a specialist mailing house and let them worry about the kit.

Stephen Hampstead, managing director of KAS Paper Systems, explained the factors a smallish printer needs to consider when deciding whether to bring kit inhouse. Addressing and Mailing Systems (AMS) also pointed us to its online guides aimed at customers.

A lot of it comes down to what you are sending out and how soon you need it, Mr Hampstead said: ‘It’s how you define small quantities too. Are you putting two pieces into a document or 12? Two or three is more likely than 12. Printers without their own mailing systems get a feel for the volumes by the fact that they’re taking in the print work, and they know too if they are sending it back to the client for mailing or they are sending it onto the mail house on behalf of the client.

‘Therefore they could say to the client “actually I could save you some money because you are passing it onto them, it’s taking longer to get out and you’ve got the cost of transportation between us and the mail house. We can do it for you at X per envelope.” It means that the printer can certainly improve his turnover and he’s probably improving his margins too, because another middleman is cut out.

‘If you’re sending the work out the chances are that you’re doing it as a service and you might not make much mark-up on it. But you do it to keep your customer happy. It’s a chicken and egg situation: should you get the volume first and then get a machine, or get a machine first and then work to get the volumes for it?’

Also the type of work needs to be considered, he added. ‘You’re looking at volumes, but it also depends on the clientele. You want data integrity and you may not be sure you’re getting that if you’re sending it out. You’re not at the mail house every day of the week checking what they’re doing with the paperwork and how they’re doing it.

‘Some mailings are very personalised, so you don’t just have a “Dear Sir” on the front letter, you have a “Dear Mr Smith” and it could be that two or three items also have a Mr Smith. Therefore you have to match with cameras, or you might do it by hand because that sort of equipment is quite expensive.’

If you are only offering window envelopes then the folding and inserting process is relatively simple. However, some customers prefer non-windowed envelopes, sometimes for security and sometimes because it gives them more flexibility on the document design. This gets more complicated because you need to address the envelope or labels or the fly, normally triggered by a barcode on the top letter. Inkjet addressers are optional on a lot of envelope insertion lines, but the capital cost, the software and the complexities of setting up and running all increase.

Another benefit of digital printing is quick turnround, and many printers offer a same-day service. This often means they need to bring finishing inhouse rather than using trade services, so the same case might be made for mailing.

Probably same day would become next day, said Mr Hampstead. ‘If someone delivers a job in the morning and they want it printed and sent out that same afternoon, then that’s difficult to achieve if you’re going to have to send it to someone else. But it’s possible if you do it yourself.’

Lower cost envelope inserters start at around £6000, but the lower end of what might be thought of as serious lines from most suppliers offer about 4000 to 6000 mail pieces per hour with starting costs typically in the £20,000 to £30,000 range.

There’s a lot more to it than pure speed of course – the bigger factor is the number of document stations that can be supported, and whether you can have (or need) inline folding. Speed of changeover then becomes another factor to take into account: more automation aids efficiency but usually adds to cost. A really low cost system might only have one station, while top priced models may go to 12, 24 or even 32. The vast majority of mailings will not need more than four: you may want the option for more as a comfort factor, or you might decide that above a certain number you are better off going to a mailing house.

‘We do have lower priced machines, sub-£30,000 for someone who wants to get into mailing,’ Mr Hampstead said, ‘but generally people will ask themselves, right, I’m spending X amount a year on mailing, say £10,000, so could I save some money by doing it myself, and having got the machine myself, can I go out and sell it some more? If I can make more use of the machine, then the ROI on it becomes much better. Because once I’ve got one I’ll be more keen to do this sort of work.’

Another beauty of digital is that it can print personalised items in mail sort order, if you’re mailing out nationally. For addressing these, the easiest method is by barcode readers, said Mr Hampstead. You then need to visually distinguish different postal region sets on the output from the mail line. ‘Some people do it manually and they look at that through the exit conveyor of the enveloper,’ he said. ‘But that’s slower because it depends on the naked eye. Most people can read a barcode on the personalised envelope, but it tends to be on the addressed document and that’s diverted, or there’s some sort of batching put into the stacker so you can clearly demonstrate one area from another.’

Speed doesn’t seem to be the biggest factor, so much as features and capabilities. ‘Mailing systems offer 5000, 6000, 7000 per hour. So depending on the size, a 10,000 or 20,000 piece mailing doesn’t take too long.’ So you can start the mailing run before the printing has finished, points out Mr Hampstead: ‘If you think of the average print speeds of many digital machines then it’s often quicker to mail out than to print.’