Pesonalised sample gift cartons and items printed on the Screen Truepress JetSX inkjet at RCS in Retford

New carton printing and finishing kit may herald the next digital revolution, in the packaging supply chain. Simon Eccles provides a quick status update on the main contenders.

We are now on the verge of a potential supply chain revolution in folding carton packaging, though it is hard to see much awareness of this out on the buying side of the market yet.

Digital presses have been announced that can handle the heavier weights and larger formats needed by a lot of retail packaging. They are aimed at a so far largely theoretical requirement for short run, on-demand and even personalised carton packaging.

Some 20 years ago it was obvious to industry commentators that the early web fed monochrome digital presses could change the whole way publishers operated. They could switch from ordering long runs of new titles and paying to keep them in warehouses for years until they all sold, to being able to order shorter runs ‘just in time’ as the books were sold. But while specialist and academic publishers were quick to take advantage, it took years before the larger publishers showed signs of understanding this potential.

Likewise today, there is little sign of the big retail-oriented brand owners thinking much about on-demand packaging yet, though in many ways they are in the same situation.

Maybe it is the way digital carton packaging is being pitched, emphasising short runs and personalisation potential. This is selling the process short, for apart from occasional promotions and novelties (personalised Valentine chocolate boxes for example), there is not going to be enough individually personalised packaging work to hang much of a business on.

Instead, frequently repeated short runs for just-in-time re-ordering has far more scope, especially when combined with regional or single-store limited time special offers. It also allows fast response to events in the wider world: the next time Accrington Stanley reaches the FA Cup final, retailers could have celebration beer packs in the local stores in the week before the match, then celebration packs for the winning team.

Purpose-built digital carton presses that can produce economical runs in the five or ten thousand range, rather than millions, would be suitable for this sort of work.

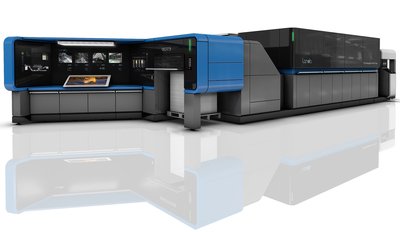

For instance Canon, via its Océ subsidiary, already has a 711 mm wide web fed cartonboard liquid toner digital press that can output the equivalent of 7200 B1 sheets per hour. The first one is with a commercial user in Germany and is CMYK only, but in future there will be more colour stations offered.

The first Landa Nanographic press, the B1 format simplex S10 FC, is aimed directly into the carton market and may reach test sites later this year. It will output about 6500 simplex B1 sheets per hour, with four or eight colours. The really interesting aspect of this technology is its founder Benny Landa’s prediction that it will be able to match offsetcosts-per-copy for medium runs up to 5000 sheets, with aims to get this to 10,000 and above later.

Glossop Cartons produced these filigreed cartons on its Highcon Euclid for its Halloween themed open days last October.

Glossop Cartons produced these filigreed cartons on its Highcon Euclid for its Halloween themed open days last October.

Other digital carton presses announced to date are sheetfed B2 formats, the majority being inkjets, including the Fujifilm Jet Press F (there is one in Fuji’s Brussels showroom), Konica Minolta KM-1 (shown at drupa 2012 and due for commercial launch at Ipex), MGI Alphajet (announced at drupa but not yet shipping) and Screen Truepress JetSX (shipped at drupa 2012 with one UK user so far). The HP Indigo 30000 B2 sheetfed carton press uses the company’s liquid toner offset technology and is just reaching Beta users.

The established Xeikon 3000 series of simplex web fed toner presses are mainly intended for labels, but they can print on cartonboard reels up to 350 gsm and 550 microns.

The 3050 and faster 3500 presses take webs up to 515 mm wide and so can handle large cartons of effectively unlimited length.

However, there are a lot of smaller digital presses already out there in commercial print sites. Can they start to offer short run carton work, in the same way that many offset printers do the odd bit of cutting and creasing even if they are not into high volume packaging?

Up to a point. Most existing digital press installations are in the SRA3 format range. This confines them to smallish box work, such as cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. Earlier models tend to be limited to 250 gsm weights, but increasingly newer models can take 300 and even 350 gsm, though usually without auto-duplexing (which is not needed for cartons anyway).

Cartonboard can go down to 160 gsm, but these lighter weights are going to be too floppy for anything other than fairly small cartons. You have also got to consider cartonboard thickness, which tends to be 300 to 800 microns and may be too much for some presses.

Carton work is certainly stressed by Kodak with the current NexPress SX sheetfed models, which have options to take long sheets of either 356 x 660 or 356 x 914 mm, with up to 350 gsm. Xerox iGen4 toner presses can handle sheets up to 364 x 660 mm and 350 gsm. MGI can handle sheets up to 330 x 1020 mm with its Meteor DP8700 XL toner press, but the maximum weight is 250 gsm.

The new breed of B2 and B1 carton presses will handle thicker calipers and weights up to 500 or 600 gsm. Even if you are not printing large boxes all the time, the bigger press formats will still give you more flexibility with nesting complex shapes, as well as the potential for mixing and matching several jobs in the same run. There is also the machine direction of the board to consider: larger sheets give you more scope to get the best carton alignment.

Also worth a mention are the faster types of flatbed printer such as the various Océ Arizonas and Fujifilm Acuity models (they are the same thing with different badges and software), or the Durst range, Inca Onsets and the Screen Truepress Jet W1630UV and higher throughput W3200UV (also made by Inca).

These can print large boards very quickly, some with autoloaders and unloaders, so they may be suited for modest carton runs. On the other hand, their UV inks may be an issue for primary food packaging.

Landa claims that its forthcoming B1 S10 CF press will match offset costs up to 5000 sheets

Landa claims that its forthcoming B1 S10 CF press will match offset costs up to 5000 sheets

Conversion drive

Digital carton presses are only a part of the story. Even more important is the conversion stage, the finishing processes that take flat sheets, cut and crease them, then fold and glue them if needed.

Boxes for a particular brand will tend to be the same shape however much you change the printed image on them. This is due to a combination of several factors, including brand recognition but also the practicalities of transport and shelf-stacking.

This argues in favour of the long established carton finishing method of metal dies.

Although the dies are expensive and take several days to make, they can then be reused many times. Bobst with its autoplaten models dominates the market for high volume carton conversion work and these can now be made ready in a few minutes, making them suited for short run work as long as you have standing dies.

However a lot of commercial printers will already have a few old clamshell platens and converted letterpress flatbed cylinder presses which they use for more occasional die cutting work.

This is where the new breed of high powered laser cutters might find an opening. They do not need metal dies, so they can provide fast response and easy ganging of multiple different jobs side by side. Because the focused beams sweep across the whole width of a job in fractions of a second they are able to keep up with at least some of the digital presses, and inline configurations have been demonstrated.

While there may be little call for variation in overall carton shapes, lasers can also be used to cut variable-shaped windows and perforations, or to add security codes. However, lasers cannot form true creases.

They can score channels, although this may weaken the carton structure. The only exception is the B1 format Highcon Euclid, which has lasers for cutting but creates extruded polymer rules for true creases using an inline impression cylinder. These are faster and cheaper to make than metal dies but cannot vary during the run.

The X-Y type plotting/finishing tables are much cheaper than laser machines size-forsize, but a lot slower too. Most can be fitted with tools to form true creases as well as cuts.

As Paul Bates, regional business manager at Esko points out: ‘They’re not going to keep up with digital presses’ for anything other than really short runs. On the whole they are best suited to prototype packaging work or test marketing runs.

Special colours

An issue that is often raised when talking about digital carton printing is special colours.

Brands are finicky about house colours, which often cannot be matched with offset CMYK, hence the multiple units of offset carton presses. Some digital presses, particularly inkjets, have a significantly wider CMYK gamut than offset inks so they will be able to match an extended range of colours. The MGI Alphajet carton press will have six colour channels for wider gamuts.

So far only HP Indigo liquid toner presses can run specially mixed ink colours, though most users prefer to run the IndiChrome extended-gamut six colour process set. The Canon Océ InfiniStream liquid toner carton press can be specified with extra colour units, though the company has not said much about what they will be yet.

Ready to risk it?

So, is there scope for commercial digital printers to break into carton work? Just about, though as we have seen, existing SRA3 printers limit the type of work that can be handled.

On the other hand, all the B2 digital carton presses announced so far have been priced at well over £1 million, and the Océ InfiniStream may well approach £3 million. That is a heck of a lot to risk on a market demand that may take years to emerge.