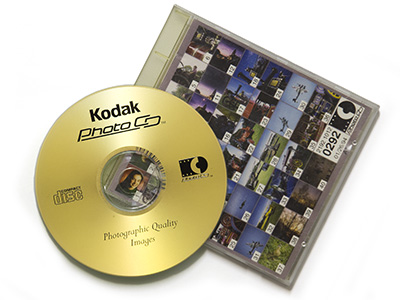

Photo CD was first announced in 1990 and was live in 1992. This 1994 disc from the author’s collection still works and contains 100 high quality scans.

Simon Eccles examines the reasons for Kodak going into Chapter 11 and looks at its digital history and prospects for its future in printing.

Last month was probably one of the worst of Eastman Kodak’s 131 year history. On 19 January it announced that it was entering Chapter 11 of the US bankruptcy proceedings, giving it protection from creditors while it restructures.

This doesn’t mean that it is actually insolvent: it expects to re-emerge next year: by then it hopes to raise a few billion dollars from patents while it slims down, restructures, and sheds some pensions liabilities.

‘There will be no significant change in our path,’ Chris Payne, vice president of marketing and director of business to business marketing, told Digital Printer. ‘Chapter 11 strengthens our funding and we are continuing to invest in R&D for the long term.’

Chris Payne.

Chapter 11 only affects Kodak’s US operations, and for the UK it is officially business as normal, he said. ‘In the short term for our customers we continue to operate as normal on a daily basis, for the supply of consumables such as inks, toners and plates.’

Ten days before the Chapter 11 move, the company announced a major restructure of its operating units, reducing them from three to two: Commercial and Consumer, with industrial printing systems well to the fore. See the box: New operating structure.

At the start of January The New York Stock Exchange threatened the company with de-listing unless its common stock price improves from below $1 within six months. The past year saw the price tumble from an unimpressive $5.60 or so to less than $1.00 by early December. In the 1980s and 1990s its share prices often topped $80.

The company made its maximum revenues in the early 1990s, and the last decade saw a steady decline in earnings. Since the current CEO Antonio M Perez joined from HP in 2005 it has only made a profit once, in 2007.

Mr Perez instituted policies of building up digital systems in both consumer and professional/industrial sectors, while closing film factories, selling off ‘non-strategic’ bits of the business, and reducing the workforce by about 47,000. In an attempt to bring in cash, Mr Perez tried selling off the company’s extensive patent portfolio in digital photography, while gingering up the market by occasionally threatening smartphone makers with legal action over alleged infringements.

However the patents sales dried up, film sales declined fast and in November the company predicted a loss of $400 to $600 million, twice its previous estimate. Chapter 11 is a bid to buy time and protection while it restructures and tries to flog off more patents.

Print patents not for sale

Mr Payne stresses that the patents that are for sale only concern photography: ‘Kodak has strategic patents in digital printing. We do not intend to sell them and we intend to develop further products and bring them to the printing industry.’

Like many once-large companies that have had to downsize, it also carries huge pensions liabilities. Alongside Xerox, it used to be a major employer in its home town of Rochester, New York, but staff levels have plummeted in recent years. It’s reportedly down to about 7000 now, out of a total worldwide workforce of around 18,800. Employment in Rochester peaked at around 60,000 in 1982. Chapter 11 will apparently allow it to reduce its pension liabilities to some extent. Or as Mr Payne puts it more obliquely: ‘In general Chapter 11 is making sure we have the right business structure and making sure the legacy costs are right for the size of the business.’

So how did it come to this? The financial and popular press rather glibly took the easy option of blaming the company’s inability to transition from the ‘yellow box’ mass market consumer film market into digital cameras. This largely ignored the huge graphic arts business, where it has long been a major supplier of films, plates, digital pre-press and latterly digital presses.

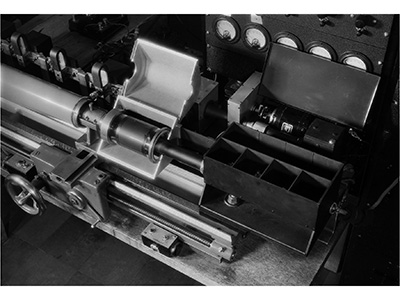

Kodak developed this drum scanner prototype in about 1935.

In fact Kodak embraced digital technology early and often for decades, across the range of image capture, processing, storage and output. Its technicians came up with potential world-beaters time after time. The problem was never that it didn’t develop digital technologies soon enough, rather that it invented them early but wasn’t able to develop the markets before rivals came along and did it properly.

The upper management rarely provided consistent support long enough for these systems to gain traction. From the 1980s throughout the 1990s there seemed to be digital strategy reversals every 18 months or so, every time the management pack was shuffled.

The company has a credible claim to have created the first digital camera prototype in 1975, but more importantly it was certainly the first to introduce a commercial professional-level digital SLR camera, the DCS 100 in 1992.

The DCS, later renamed DCS100.

As news photographers started going digital in the late 1990s, it was initially the rapidly advancing DCS models that they chose. But once Canon and Nikon worked out how to build their own high end digital SLRs around 2000, Kodak was squeezed out of the pro market and concentrated on consumer digital cameras. It did well there at first, and early in the past decade was US market leader with its EasyShare series. Only with the advent of cameraphones did it really lose out. It outsourced camera manufacture and last year sold its well-regarded camera sensor business. Now it’s alternately suing cameraphone makers and offering them its patents.

Another early digital breakthrough was Photo CD in 1992, a very well thought out consumer and professional system that offered cheap high res scanning of colour film onto CDs. This put the wind up pre-press scanning houses at the time, but Kodak let Photo CD wither away after a few years.

A Photo CD sample image from 1994. Although no longer supported by Kodak, the CD is still usable.

In the early 1990s the company managed to get halftone digital proofing working via its Approval system, but at such a high cost that the commercial print market went for cheap contone inkjets instead. Approval did attract packaging printers thanks to its ability to transfer onto most materials including card, film and foil, and it is still available.

Professional printing

Kodak has built and retained a large and significant presence in the professional print industry sector. Until January this was called the Graphic Communication Group, but it’s now part of the new Commercial Segment.

The professional print side has three major product families, linked by shared production software. The company has extensive offset and flexo plate manufacturing facilities (as well as graphic arts film), giving it significant consumables revenues. These latter were largely created inhouse, but with additions from Polychrome (run for a while as Kodak Polychrome Graphics) and the 3M graphic arts spin-off Imation. Its offset and flexo platesetters are descended from CreoScitex, which it bought in January 2005.

The company was a successful maker of high volume monochrome analogue photocopiers in the 1980s, giving it experience to develop the Digimaster digital production printers in the 1990s, whose descendents are still important players in the market. High end digital colour toner presses came with NexPress Solutions, originally a joint venture with Heidelberg, which first showed prototypes at drupa 2000. Heidelberg pulled out in 2005 but NexPress carried on successfully without it.

A couple of years ago Kodak proudly announced that it had been working in inkjets for 40 years. This was true up to a point, but the original pioneer was Mead Digital Systems in Dayton, Ohio, which developed continuous flow inkjets that it brought to market in 1972. Kodak bought this in 1983 and renamed it Diconix. It developed the successful 3600 continuous flow monochrome inkjet overprinters for newspapers, direct mail and the like.

However in 1993 Kodak sold Dayton to Scitex for $70 million, which operated it for the next ten years as Scitex Digital Printing. Under Scitex, it developed the first Versamark standalone reel fed inkjets, mainly used for transactional work such as utility bills. Full colour configurations offered modest quality but high speed and good economy.

A decade later in 2004 it bought Scitex Digital Printing back again for $250 million. Since then development money has led to new Versamarks and, most prominently, the Prosper Press family of high quality, high speed production inkjets. These are selling well in monochrome configurations, with full colour models starting to see installations too.

Kodak is naturally enough determined to put a positive spin on its situation. It really does have a strong position in commercial printing systems and consumables, with no reason to doubt that this segment is viable. It has revealed that its offset plates, film and workflow software business is worth about $2.5 billion per year. Digital print operations plus packaging are worth around $600 million. Document imaging (scanners) and various enterprise and brand management software solutions bring in another $500 million.

The prospects for its digital presses seem good, though colour toner and inkjet models are all high end and thus pricey – the lack of lower end entry points is a weakness. Colour Prosper Presses seem to be reaching the market rather slowly compared to HP’s rival T300s, though European marketing manager Erwin Busselot denies that there’s any problem and claims that the company is shipping Prosper 5000XLs as fast as it can built them.

Actually, the print business looks healthy enough that it could hypothetically be packaged up and sold, though it’s hard to imagine who could afford it in today’s economy. But digital could possibly be spun off separately from plates and film. After all, Dayton has been sold before.

Mr Payne denies that this is in prospect. ‘Digital print is the core of the new business,’ he says. ‘We continue to look at the sale of non-strategic businesses. But we will move forward into our core industrial businesses, which includes Prosper and the other digital print systems. We see offset and digital co-existing for a long time, and we continue to see modest growth in offset, especially as runs become shorter.

‘Graphic communications is vital to our future and we continue with all current plans, including drupa. We will show new technology, new Prospers, new workflows.’

New operating structures

On 10 January Kodak announced a reorganisation of its major operating segments. In what it claims is a simplification, three business segments are being merged into two big ones: Commercial and Consumer. These will report to a new Chief Operating Office.

The Commercial Segment incorporates the former Graphic Communications Group, which largely deals with the professional printing sector. Collectively these parts brought in revenues of $3.5 billion in 2010.

This includes printing plates and films; the pre-press imaging systems; workflow and related software; the Dayton inkjet press developer (responsible for Prosper and Versamark presses and inkjet heads); and the sheetfed toner press business (the NexPress and Digimaster lines).

Also part of the Commercial Segment are two parts of the former Film, Photofinishing and Entertainment Group (FPEG): Entertainment Imaging and Commercial Film. Apparently the manufacturing processes have a lot in common with plates and film for print.

The Consumer Segment will include all of the former Consumer Digital Imaging Group (ie low end digital cameras and home printers) plus three former FPEG product lines – Paper & Output Systems, Event Imaging Solutions, the Consumer Film and Intellectual Property businesses. Collectively these brought in revenues of $3.7 billion in 2010.

The senior management has also been reshuffled to take account of the changes, and because of some upper-level resignations at the end of last year.