Banners and soft signage are staples of the wide-format production world, covering a wide and growing range of applications. The materials and methods are changing too, with digitally-printed textiles coming up fast as an alternative to stalwarts like PVC for a number of reasons, finds Michael Walker.

By sector, the uptake of digital print technology is more advanced in the various wide-format applications than anywhere else, except perhaps ceramics, which flipped rapidly to digital as soon as speed, quality and reliability issues around digital printing were solved. It has been a similar story with signage and display – the set-up costs of creating large printed products in very small quantities via analogue print technologies, whether via screen or litho printing, meant that as soon as digital devices were able to print onto the same substrates at reasonable speed and with acceptable quality, their higher ink costs quickly paled into insignificance compared to the reduced waste and preparation.

That started happening more than two decades ago, in the mid-1990s, and it is now accepted that more than half of wide-format production is now done using digital printers. One of the most enduring and widespread applications within that is in the production of banners, whether they are the kind that hang outside pubs, hotels or sports clubs, line the crowd barriers at marathons, cycling events, golf tournaments or music festivals, or are the roll-up type that can be taken to presentations and exhibitions, set up and packed away quickly and easily.

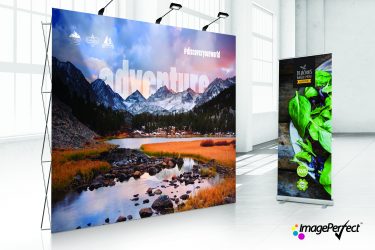

ImagePerfect textiles from Spandex suit modular exhibition and display systems

Typically these are made of PVC, which like many plastics that are now coming under increasing scrutiny as a result of public concern about environmental issues, earned its place for otherwise having all the right characteristics: cheap, light, strong, flexible, able to support very good quality print and (sometimes with suitable additional treatments) durable enough for the purpose. Initially it was solvent printed, with inks that would penetrate into the plastic, giving a vibrant and lasting result; subsequent developments in digital print technologies mean that it can also be printed with ecosolvent, UV-curable and latex devices.

Its downside is that it is not so easily recyclable (assuming it is collected in the first place and not just binned on-site) and can only be used for lower-grade purposes, though there are plenty of those, from resilient but yielding playground surfaces to pipes and window frames. As a result of the backlash against plastics, and perhaps in ignorance of these second uses being available, substrate suppliers to the sector are seeing increased demand for alternatives.

‘Demand for PVC is still strong and always will be, for the foreseeable future,’ says Soyang’s UK sales manager Tim Egerton, before adding, ‘but customers do want more environmentally-friendly options, which could be recyclable/ recycled PE (polyethylene) alternatives.’ Increased demand for alternatives like this has seen the price premium for recycled PE material drop from 30% to about 5% and the performance Mr Egerton says is as good as with new. Another area of environmental impact improvement has

been at the manufacturing stage, where reductions in the energy usage and therefore carbon footprint associated with the process have been reduced. In terms of what chemicals are used in manufacture, Mr Egerton says that all material from Soyang meet the EU REACH requirements.

Alterra from Senfa is made of recycled PET bottles and

printable via dye sublimation

Another way

An alternative to looking for materials with a better sustainability story to tell than PVC and its cousins might be to change how certain client needs are met altogether. Mr Egerton cites the example of one customer who was buying self-adhesive PVC rolls to print and mount onto rigid boards but stopped altogether after buying a hybrid printer that could print directly onto the board substrate. Clearly, a rigid board isn’t a banner in any usual sense, and there will be applications for which a flexible finished product that can be hung outdoors via grommets or mounted on poles is the only practical or acceptable option, but it is worth thinking about whether the desired result could be achieved via a different substrate and production route.

This is where textiles increasingly come in. While various meshes and other woven materials are essential for flags and soft signage anyway, the range of applications has grown enormously in the last couple of years. ‘Textile is almost king, it is in vogue in exhibition and retail work and an incredibly wide range of applications, including those that would traditionally have been done with PVC, such as cinema banners, where a 210g warp knitted textile does the job,’ confirms Mr Egerton.

‘Clients are waking up to the advantages – UV or latex print has to be rolled on a core for transport but textiles don’t and exhibition companies are looking for solutions that don’t get “travel sick”,’ he adds.

It is a similar story from Mick Crook, commercial director for the consumables division at EFI Vutek and Mimaki reseller CMYUK. ‘We’ve seen growth again, especially in textiles for specialist décor. In retail display many brands are now going for tension frames rather than sheet cardboard or stuck-on PVC. It looks better and in the larger shops the frames can be changed daily or per campaign rather than closing the store and stripping the walls,’ he says.

He too speaks of huge growth in the exhibition market, and the move towards wrapping walls or panels in printed textiles rather than using plastic cladding. ‘People are asking for textiles if the applications suits it, the environmental stance is more prevalent,’ he adds, noting that the Pongs and Berger ranges of textiles that CMYUK supplies are polyester rather than PVC, though the company does supply PVC under its own brand, which is made in Europe and mostly used in solvent-based printing.

In the warp and weft

Polyester-based textiles work with dye sublimation printers, and this type of textile is what both Soyang and CMYUK supply, not least because it works best with flags. ‘The majority of flags are printed dye-sub because UV or latex sit on the surface, while dye-sub penetrates into the material,’ explains Mr Egerton. Within the dyesub category there are two further distinctions in how the ink is delivered to the fabric: the direct-to-textile approach is favoured for flags, according to Mr Egerton, as it drives the dye further into the fabric, which results in better colour show-through on the reverse. While this approach could not previously deliver the same quality as printing to dye-sub transfer paper and then running printed paper and receiver fabric through a calender to transfer and fix the dye, Mr Egerton says that it has now caught up.

Mr Crook adds that the direct-to-textile mode is generally used but for stretchy fabrics, as are being increasingly used to wrap display stands, the transfer paper and calender route is preferred as the fabric only has to pass through the latter. He says that ongoing developments in the materials are aiming to improve opacity and image quality when stretched or used in block-out applications, and cites Pongs’ Elastico as a good example of this. He says that customers in retail prefer dye-sub print for a more natural look, ‘especially on anything stretchy, pillowcases, flags or voiles’, while exhibition clients tend to go for UV-cured.

Envirotech from Innotech is PVC-free but said to offer similar outdoor durability

As a hardware supplier too, CMYUK also finds that customers are often looking for inline systems, as found in the EFI FabriVu range, rather than having a separate printer and calender, especially if they already have a UV-curing printer: ‘They’re used to having the UV machine and want something similar to stand next to it,’ he comments.

Innotech is another supplier that has seen demand for PVC-free products increase, especially over the last six months, according to marketing manager Kieran Dallow, who says: ‘Our Envirotech PVC-free media range means we can easily fulfil these demands with banner, blockout and mesh materials all made from alternative materials to PVC, yet retaining the durability in both the indoor and outdoor environments that PVC banners have become known for.’ Leon Watson, general manager UK at Spandex says: ‘Digitally printed banners and soft signage applications are one of the fastest growing areas of the market. Spandex delivers a number of banners, ranging from economical 440g products to premium 800g double-sided blockout options.’

He adds, ‘The assumption that there is a high price point for entry into the soft signage market, and in particular textile printing, due to the need to purchase expensive dye sublimation or super-wide format printers is something of the past. We offer a variety of textile materials within our ImagePerfect range, which are suitable for printing on ecosolvent, solvent, UV and latex printers.’

Another PVC alternative comes from French manufacturer Senfa whose Alterra fabric is woven using recycled fibres and then coated to give a smooth printable finish, which the company says ensures “stunning” backlit graphics with all necessary fire retardant properties. The material is made from recycled PET plastic bottles; every tonne of PET bottles that is recycled is said to equate to nearly 2.3 tonnes of CO2 emission reduction.

Senfa also manufactures Sublimis, which won an SGIA award earlier this year. It is a textile material designed for backlit dye-sub imaging but is claimed to be lighter (and thus cheaper to transport) than uncoated alternatives, as well as easier to install. It is also claimed to have excellent light diffusion and like Alterra, is available in the UK through Soyang. dp