Cloud computing is one of those technology buzzwords that’s come to mean a variety of different things. In the first of a two-part series, Michael Walker peers through the mist to see which of them are relevant for digital print.

Technology mega-trends like the rise and adoption of the internet have had a major impact on the print industry and a lot of it hasn’t been positive, with profitable print work disappearing in favour of online alternatives. But it has also brought benefits in terms of news ways of reaching customers, attracting, allocating and managing work, and even enabling entirely new business models that didn’t previously exist.

A child of the internet that’s been a major trend in the IT world for several years now is cloud computing and unsurprisingly, workflow and other software developers active in the print industry have looked to adopt and exploit some of its capabilities. But the term is used in a variety of contexts and ways that aren’t the same, leading to confusion and perhaps sometimes rejection of something that does merit closer consideration.

So what is it?

If the internet is ‘the cloud’ (so called because that’s how it’s often represented on conceptual diagrams that differentiate between what’s inside an organisation’s premises or network and what’s outside), then cloud computing means doing the processing or computational heavy lifting on the internet. So instead of running suitably specified servers, PCs or Macs on-site, you pay to use processing services elsewhere on the internet, sending whatever data is required for the job and receiving the results back the same way. That might involve connections with MIS, production workflow, e-commerce portals (which themselves may be hosted outside your business), CRM or other databases, but would usually be accessed and controlled via a web browser interface, making connection from anywhere and on a wide range of devices possible.

Ricoh Supervisor provides insight into individual press performance as well as a top-level overview

The benefits are that you don’t have to pay for, upgrade or maintain the hardware itself, so there’s no up-front investment or unexpected breakdown costs; the software is also kept up-to-date, patched or otherwise improved by someone else with no effort or additional cost on your part. Rapid deployment and scalability are also touted as attractions – some services can be up and running in hours and if you know there’s a production peak coming you can rent more capacity to help deal with it and scale back afterwards. In theory, you only pay for what you use. There are also some benefits for the software developers – everyone is automatically kept on (more or less) the same software version, which simplifies support, as upgrades and bug fixes are effectively rolled out to everyone without being dependent on users to update.

The downsides are mostly related to the potential impact of communications failure – complete loss of internet connection or reduction in bandwidth that could stall or slow production, and data security, particularly in the light of GDPR. Most hosted service providers will argue that the purpose built server farms operated by the likes of Google are both more reliable and better protected than anything most printers are likely to run on their own premises, but some users are still uncomfortable with the idea of their data being on ‘shared’ servers, wherever they are. ‘There’s a level of trust needed re mission-critical parts,’ says John Davies of Fujifilm Europe, which provides the ColorPath online press profiling service. He also suggests that there is more mileage in developing new tools online. ‘In the realms of dashboards and analytics there seems to be a next generation of products; reworking old ones into the cloud seems to have little traction,’ he says.

There is also the more philosophical questions of who ‘owns’ the software or service. While conventional on-premises software licensing has never transferred ownership, it has allowed a perpetual licence to run a given version. With the software-as-a service (SaaS) rental model that cloud offerings use, you’re only ever paying for a given period – stop paying and you lose access to the service (and possibly the data too). ‘Printers do like to own stuff and some are really against the subscription idea,’ comments Mr Davies.

That’s what might be called ‘pure’ cloud computing, but there are related models that make use of or entirely depend on the internet but which don’t involve the production processing being done somewhere in the cloud. The SaaS idea can be applied to software that runs on your own computers but which is paid for a on rental basis and updated from the provider’s side. Adobe’s Creative Cloud is a good example of this – you still run the applications on your own hardware but you pay a monthly fee for the use of them, which includes all the updates and support. The generic ‘as a service’ concept has spawned a whole range of buzzwordy derivatives, including ‘platform as a service’ and even ‘device as a service’. Whatever bizarre language contortions they may involve, they’re all rental models, whether what’s being rented is actually use of a service performed remotely via the internet, or a piece of hardware that sits on your desk.

Simon Tapley of Ricoh Europe

E-commerce connectors

Another related category is what might better be called internet-enabled services. These build on the interconnections that the internet makes possible to provide services that can’t really be provided any other way. The best application in print is the print broking service offered by Cloudprinter or 360 onlineprint. Both of these essentially connect print buyers with print providers in a controlled and vetted environment, and provide central routing and job allocation capabilities to make the best matches between customer requirements and print capacity, taking into account a number of factors. Job assignment takes place ‘in the cloud’ (on the software developer’s servers, wherever they may be; customers and printers don’t need to know or care) but job files aren’t processed there, the usual prepress and production is still done at the printer’s site but with reporting flowing back to the service’s hub for tracking, analysis and customer updating.

José Salgado, co-founder of 360 onlineprint describes his business as an e-commerce marketplace. It has no design, print or production capability itself; all these functions are outsourced but as Mr Salgado explains, ‘We control the supply chain with full tracking of orders – we can see the purchase, the production partner. The 360 software does the tracking and logistics, all through the cloud.’

More than just matching buyers with sellers, 360 onlineprint has developed its own ‘intelligent marketplace’ software to aggregate and optimise production across a network of selected production partners, from prepress through to shipping. Mr Salgado says that standardised products can make their print partners’ businesses more efficient; the latter receive pre-prepared imposed or nested PDF files with JDF information from 360 into their production systems so all they have to do is print, finish, pack and ship. As well as matching product type and capacity criteria the 360 system aims to enable production as locally to the end recipient as possible. The company, which is headquartered in Portugal, and serves European customers from there, also has print partner sites in Brazil and Mexico, for example.

KM’s Caroline Raine

The idea is to achieve competitive costs for end-customer by automation and enhanced efficiency. ‘We don’t need to impose prices on our partners, we are their most profitable customer,’ claims Mr Salgado, adding that they provide a constant flow of orders which the printers may use to fill night shifts or other quiet times. He also reports being overloaded with enquiries from prospective UK print partners but says ‘we look for providers with the quality, commitment and who are efficient in terms of process.’

A similar idea lies behind Cloudprinter, which aims to provide a level of automation in linking online print customers to print providers via a pair of APIs to source and route jobs. The Print API integration (for buyers) can be with e-commerce platforms such as Shopify, WordPress and Magento or to internal systems at the customer’s site such as SAP databases or publishing systems, while the Production API (for the print partners) links with the press, workflow or MIS. Cloudprinter has a relationship with Enfocus so that the software can connect to the latter’s Switch workflow automation software and makes registration and connection a simple process. It too works with Zapier.

Cloudprinter has a job routing algorithm that allows a wide range of preferences such as type of press or product speciality to be factors in the decision. ‘It could be a printer with an Indigo 7600, or a Nuvera for mono work, or who has PUR binding,’ explains co-founder Martijn Eier, who stresses that Cloudprinter provides purely the API ‘backbone’ of the service; a white-label version is in development so that print partners can use it with their other clients. Cloudprinter gathers data from the network and so can build a picture over time of how various factors combine to produce good performance, the effects of price drops (the service lets printers set their own prices but does advise what volumes they can expect), and what types of work are sustained and profitable. At the time of writing, there were 157 print partners supporting 420 job templates and 5000 product options, deliverable in 104 countries. Mr Eier is on the look-out for more UK digital printers to join, covering large format, commercial print and book work.

Cloudprint founder Martijn Eier

Campaigns on tap

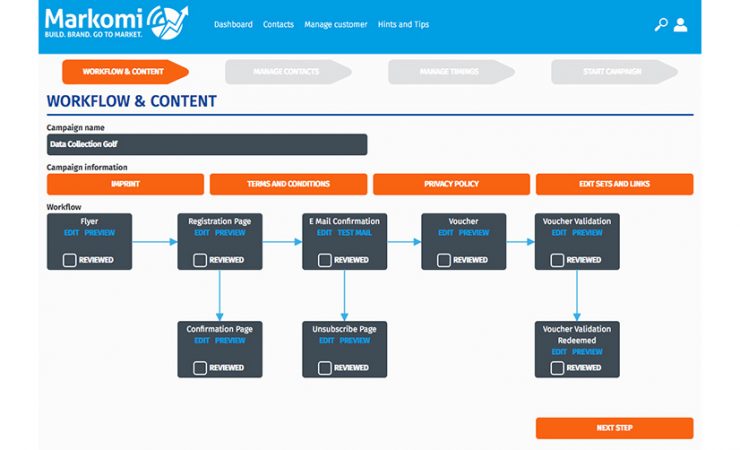

Konica Minolta is this month launching Markomi, a template-based cloud-hosted multi-channel campaign creation and management tool that allows printers to offer their clients complete cross media marketing campaigns that include email, QR codes to link to personalised landing pages, SMS, print and even fax, while managing and simplifying the data and digital channel aspects of doing so.

‘Customers can amend the campaigns the printer offers,’ explains KM Business Solutions Europe’s Caroline Raine, adding, ‘They can edit workflow, add special offers or data collection without [needing] marketing knowledge or the IT infrastructure. Printers can add other chargeable services, such as augmented reality [via KM’s GenARate software] or embellishment.’

The software is offered on a pay-per-use basis, which Ms Raine says is ‘low cost, low risk’. Design skills aren’t required and visual elements can be left as editable or locked down as is appropriate for clients, each of whom can be presented with a branded portal to setup and monitor campaigns. Data collection via social media is supported and user reporting is included. It’s not essential to have a K-M press but there are some configuration advantages if you do; an early user of the software is Colourfast Financial, the first UK site for the KM-1 B2 inkjet press.

Ricoh has three main cloud solutions: Marcom Central, for planning and executing multi-channel campaigns that include variable data print, and the more recently introduced Supervisor and Communication Manager. The latter two, previewed at Hunkeler Innovationdays in February, exemplify what Ricoh Europe’s manager for software and workflow Simon Tapley calls a ‘cloud and ground’ strategy. Supervisor collects production and machine data from the ‘ground’ and being JDF/JMF-capable is not limited to Ricoh devices but can talk to finishing equipment as well as other vendors’ presses, as well as to production workflows – initially Ricoh’s own Production Director, and support for third-party offerings is planned. ‘The value proposition is that it’s a complete solution,’ says Mr Tapley.

Communications Manager is purely cloud-based and aims to tackle business organisation at the highest level, by connecting processes and software of all kinds in mid-to-large print operations. ‘It’s workflow automation but about extracting and feeding information from workflow and production to CRM, MIS, finance and customer services,’ says Mr Tapley. This has applications particularly in transactional and direct mail operations and he says is attracting attention from large print groups who would otherwise expect to have to develop bespoke software to achieve the same things. It’ early days yet for both these offerings but Mr Tapley says, ‘I would see both evolving, becoming more bespoke and offering more out-of-the-box’.

The software discussed here relates to issues around managing print or print in the context of multi-channel campaigns. In the concluding part we’ll look at tools that are specifically for production and analysis.