Colour management is about a lot more than just not getting jobs bounced because they’re obviously wrong, it’s the basis for efficient printing and a platform for adding value, finds Michael Walker

Every professional level digital press you can buy these days comes with some kind of colour management capability, either bundled with the Rip/DFE or available as an option from the manufacturer, whether it’s their own development or something they licensed from a third party. So it’s obviously something that’s expected and perhaps even taken for granted, but is it worth stepping back and asking the fundamental question ‘what is it for?’, as the answer to that has changed over the years, and particularly in the context of digital print.

Fundamentally it’s about getting colour right (though ‘right’ by which criteria will be discussed in a bit) and keeping it there from day to day, job to job and from press to press. Consultant Paul Sherfield refers to the Common Colour Appearance concept adopted by Fogra, which he says can be boiled down to ‘printing the expected’ across a range of print technologies and applications.

Andy Campbell, Ricoh, looks at it from a manufacturing perspective, saying, ‘Colour management is about lean [manufacturing], repeatability, getting the closest result.’ The efficiency idea is also embedded in a comment from Roland Kampa, senior product line manager at EFI, who says, ‘PSPs fumble with graduation curves… [when] it would be easier to schedule linearisation/calibration, but operators are under pressure to run the next job.’ Mr Kampa notes that colour management is ‘deeply integrated’ into the Fiery DFE software, making it simpler to use these features in a routine way.

Kodak’s Cloud, Color & Content Products manager, Software Division, William Li says ‘Calibration is the bedrock.’ He’s also a fan of standards, pointing out that you might need to work to a standard for a competitive bid or to please a particular customer, but that working to common standards enables companies to compete on efficiency. ‘People are waking up to the idea that the craft shouldn’t be in making the tools behave, it should be about meeting customer expectations. Consistent standards make for a better market,’ he argues.

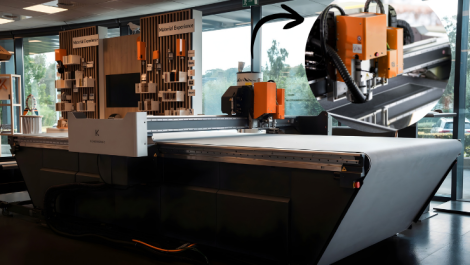

The Color Profiler Suite is at the heart of EFI’s colour management offering and is tightly integrated into its Fiery DFEs

Self-regulation

Xerox UK’s Kevin O’Donnell agrees, and advocates what he calls ‘closed loop automation’ as a way of achieving it – with presses that feature built-in spectrophotometers, he argues that getting them into a stable and calibrated state can be a ‘one-part process’ and that on-the-fly measurement and adjustment can correct for drift during production.

That idea is being increasingly adopted by other digital press manufacturers, though for some it’s an optional inline extra. Konica Minolta debuted its IQ-510 Intelligent Quality Controller in 2017, and Ricoh added the similar ACD this year, also offered by Heidelberg for its Versafire. These also look for a range of print and page defects.

Achieving stable and tightly-controlled printing conditions is only part of the story, though. Part of getting the colour right is to know how a particular combination of press, toner and substrate behaves and to tweak the values fed to the writing engine to allow for the limitations and idiosyncrasies of each. This is what colour profiles are for, and while presses ship with a range of generic ones for different paper types and print settings, they can’t cater exclusively for each press, toner and paper combination, so tools are usually provided for creating colour profiles. Mr Sherfield estimates that only around 20% of printers actually make their own profiles, however, and then usually only because of client requirements.

Ready, aim …where?

With the press stable and calibrated and the right profiles in place, the question then arises of what target are we trying to hit? There aren’t really any universal standards for digital print colour, so ones based on offset tend to be used, particularly if there’s a need to match work across analogue and digital presses. There’s the ISO 12647 series which is as much an overall quality control standard as a colour-specific one, plus more regional variants such as the Fogra standards developed in Germany and adopted across much of Europe, or the Idealliance-derived ones in the US. The Fogra profiles are specific to paper types and the recent Fogra 51 and 52 allow for the use of optical brighteners in coated and uncoated papers respectively, and are gaining traction in commercial print, though GMG’s UK product manager Paul Barnes notes that most in the packaging sector stick to the older Fogra 39L, ‘because that’s what their customers expect’.

Canon supports Fogra, Swop, Gracol and Japanese Standard input profiles and offers X-Rite spectrophotometers for calibration and profiling. Its latest PrismaSync DFEs support Fogra and G7 verification values, allowing test pages to be printed to check conformance. Business development manager Chris Aked says that most UK customers ‘adhere to Fogra standards, generally F39 or F52’. Kodak’s Mr Li suggests that between a third and a half of printers worldwide are working to some standard or other, either because their client specifically require this as a condition of winning the work or because it’s just a good way of getting predictable and efficient results.

The G7 standard, which originated in the US, is gaining ground, too. It’s said by Kerry Moloney, product marketing manager at EFI, to be easier to implement, being principally concerned with managing grey balance. ‘Fogra is more about certification, G7 is more a process,’ she comments, adding, ‘It’s easiest to maintain in the long run,’ but accepts there’s an education issue which the company is trying to address via webinars and e-learning, to promote the concept of ‘overall colour maintenance’.

HP Indigo’s Gershon Alon notes, ‘The requirement for colour standards adherence is getting lower, as result of the type and source of applications. More is being driven through e-commerce, where professional requirements are less, or are defined differently,’ though he acknowledges there is still a ‘traditional’ print base for whom it’s important.

HP Indigos can accommodate up to seven ElectroInks, allowing spot, metallic or gamut-extending colours

Xeikon offers consultancy-based support under its Custom Colour Services banner, which draws as necessary on the expertise of its Aura network of specialist partners. It’s aimed at customers running multiple sites and with multiple devices and where matching colour and/or extended gamut printing are requirements. Four levels of support are offered, from a basic site visit and recommendations, through G7 compliance with Alwan Standardizer and Verifier software, Xeikon Color Control licensing (essentially the same but without G7 tools) and the full Custom Color Services.

But there’s also a conflict with working to offset-based standards, because most toner presses can print to a wider colour gamut with their standard CMYK toners than offset so in a sense are being wasted by being restricted to what offset can achieve. For presses with additional colours, particularly neons, this is even more so (see article on page 34). For papers that do yield a larger colour gamut just with CMYK, it’s possible for Canon users to build a large gamut Media Print Mode, according to Mr Aked, but Ricoh Europe’s application and innovation manager Andy Campbell goes further and asks, ‘Why limit yourself to Fogra 51? If you’re not matching offset, you can run to a bigger gamut [and] can really push boundaries. We’ve seen some really good results done this way.’

This view is backed by Mr Alon, who points out the consistency of colour across the Indigo line, which shares the same ElectroInks and imaging technology across its various generations, speeds and formats, and says that ‘more are trying to leverage the full Indigo gamut’. This idea is supported by colour management on Indigo presses being split between the DFE, where Global Graphics technologies are used for the transformation of print data

into the Indigo inkset (which may include any additional colours, though these are treated only as spot colours), together with any manipulation needed to hit a specified colour standard, and then the media ‘fingerprint’ is applied within the press, allowing jobs to be re-routed to different machines or substrates changed at the last minute.

Series 4 and 5 Indigos all have built-in spectrophotometers and can work with the ColorBeat Cloud-based colour tracking and scoring software, part of the Print OS suite, which Mr Alon says provides a competitive aspect to company performance in this area: ‘Once this is visible, magic happens,’ he says. EFI’s ColorGuard aims to offer something similar, though without the public visibility aspect.

Printing to maximum gamut requires images that haven’t already been stripped of the colours outside offset CMYK, so usually need to be supplied in RGB, with ECI RGBv2 being a good choice for high-end print according to Mr Sherfield. GMG also offers an ‘RGB to max gamut’ conversion option for those who want to use it.

Even with an expanded gamut, hitting some Pantone or similar reference colours can be difficult, however. This is compounded by the fact that the Pantone reference guides are offset printed using specially mixed inks, so there’s an inherent technology mis-match. Doing a good job with these is central to many colour management solutions, notably those from GMG and EFI, though they’re generally less of an issue in commercial print than in packaging. Systems like Extended Colour Gamut (ECG) printing, in which orange, green and violet inks are added to CMYK to provide an all-round expanded gamut and so cover more Pantones are also used in packaging, but very few commercial sheet-fed digital presses can support this many colours in a single pass, with only HP Indigo qualifying.

Digital does digital

There’s also the proofing role, where digital devices normally simulate analogue ones for proofing or prototyping. This is where GMG initially built its business, becoming very much a technology of choice for offset proofing via Epson roll-fed printers, and the company’s current technology, based on its OpenColour model and ColorServer products still serves this market, particularly in packaging applications where not just litho but flexo may need to be simulated.

But there’s still a role for proofing in an all-digital production environment as Mr Barnes points out that it’s not always practical to stop a production machine to run off one sheet to test for a job, and staff in the prepress studio may need to test work before sending it for the production run. The OpenColor technology, which is based on spectral colour data, allows a job to be proofed for a digital press just as for an analogue one.

The arrival of additional colours such as fluorescents/ neons brings some exciting new capabilities but presents challenges, both in terms of raising client awareness of the possibilities and for prepress and production. Education is key to the former. As part of its CMYK-Plus campaign, Xerox is running what it calls Project Genesis, a mix of tools, training and webinars to help make designers, specifiers and brands aware of what is possible, which will include live in-person events from this September. ‘We haven’t gone out and shouted it from the rooftops enough,’ argues Mr O’Donnell, though he adds, ‘Clear toner now being used intelligently, as part of the design process and fluorescent is staring to become interesting; the pink on the Iridesse has caught the imagination.’

Similarly, Ricoh is promoting the creative possibilities of its additional colours via its Digital Works ‘inspiration guide’ and its Business Booster Edge online events. Mr Campbell says the usage has grown but ‘not as fast as we’d hoped. Printers have to go and market it, something they’re traditionally poor at.’

Even if you’re not in the market for printing with extra colours, colour management has a role to play in streamlining your production processes, minimising waste and giving your clients what they expect.